best shoulder treatment in chennai

SHOULDER

Shoulder instability

What is shoulder instability?

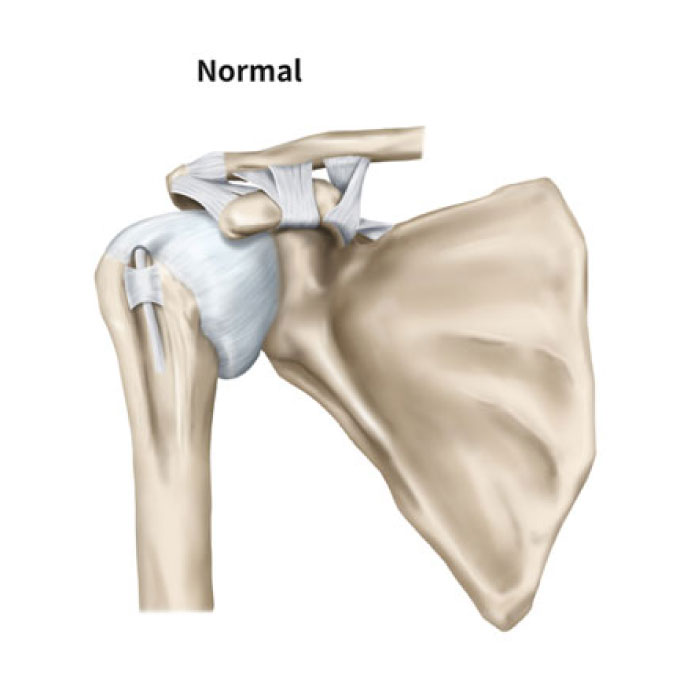

The shoulder performs a vital role in allowing us to position our hands in the space around us, in order to perform the variety of tasks that we perform during our daily lives. As the ball and socket joint of the shoulder (known as the glenohumeral joint) is so mobile, this makes it one least stable joints in the body.

The ball and socket joint of the shoulder (known as the glenohumeral joint) can be come unstable after high energy trauma, such as during a fall or a tackle, where the structures that normally control its stability are torn. In individuals with a high degree of flexibility (sometimes known as generalized hypermobility) the shoulder may be inherently lax or become more troublesome after minor or more repetitive injury.

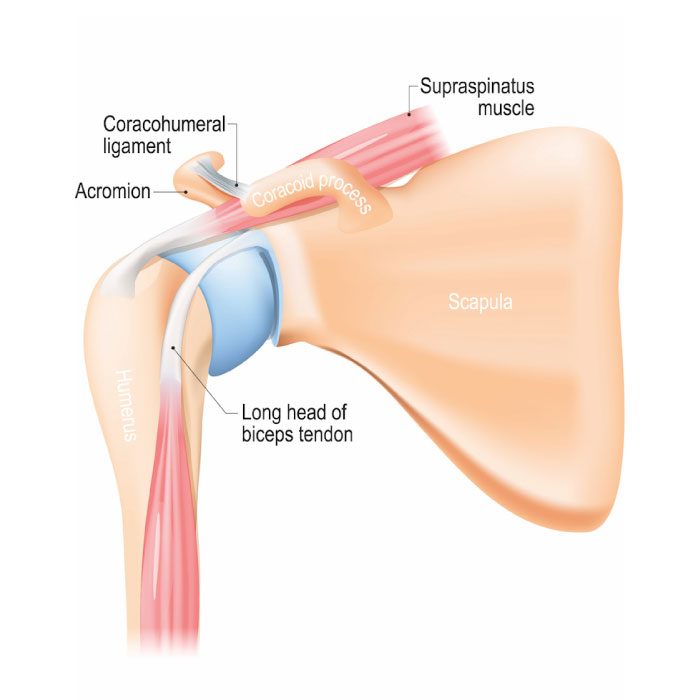

To provide stability, the shoulder relies on the labrum (the lip liner that deepens the socket); joint capsule and ligaments, as well as the co-ordinated action of the muscles around the shoulder. In a traumatic shoulder dislocation, the humeral head (ball) is usually dislocated anteriorly (to the front) out of the glenoid (joint socket). This commonly results in tearing of the labrum and damage to the ligaments.

In certain arm positions, this may result in these structures becoming unable to help contain the head in the glenoid. In some cases, the anterior rim of the glenoid can become fractured and this can make the symptoms of instability worse.

The appropriate treatment for shoulder instability is dependent on a number of factors including the type of instability; the pattern of structures injured, and the anticipated types and levels of activity that the individual wishes to undertake. In a traumatic instability, it may be necessary to repair the damaged structures, with either an arthroscopic stabilisation (keyhole surgery), or open procedure. Physiotherapy is also necessary following surgery to rehabilitate the shoulder.

If the dislocation has occurred without trauma, or with only minor trauma, or if the age and activity levels of the individual make further dislocation unlikely, it may be that the instability can be treated successfully with physiotherapy.

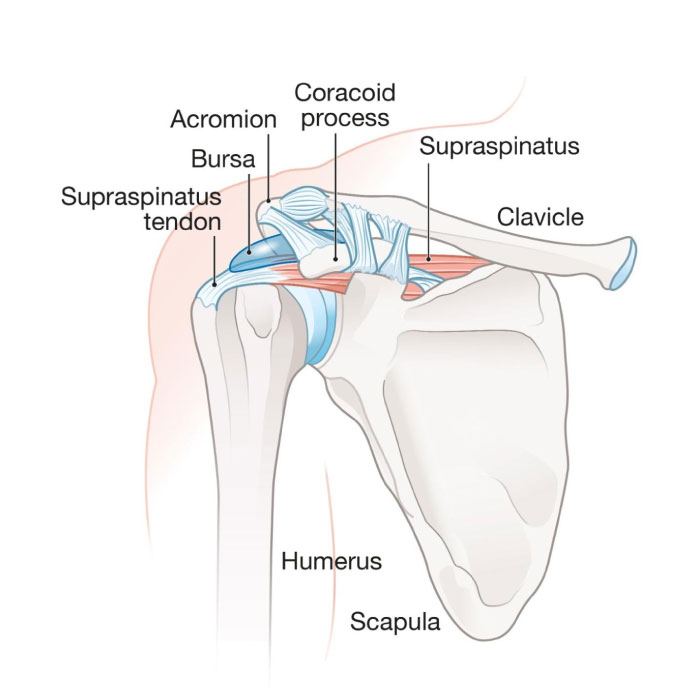

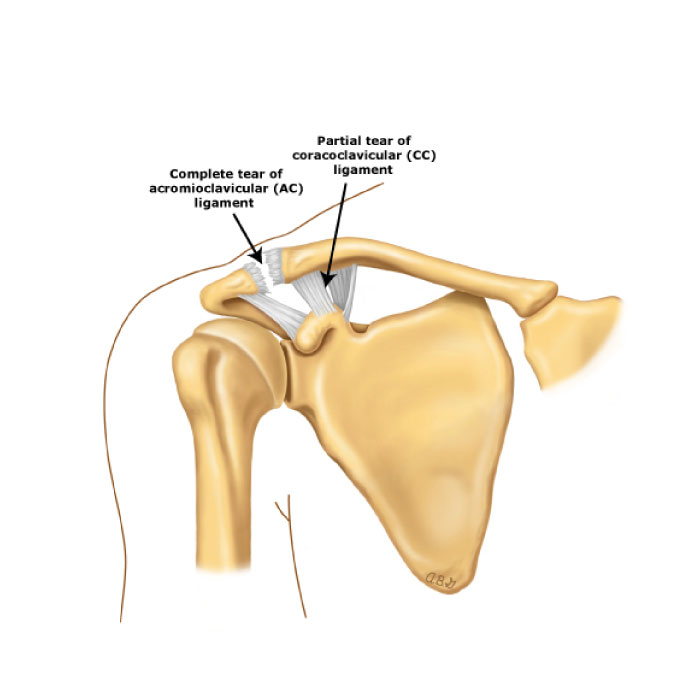

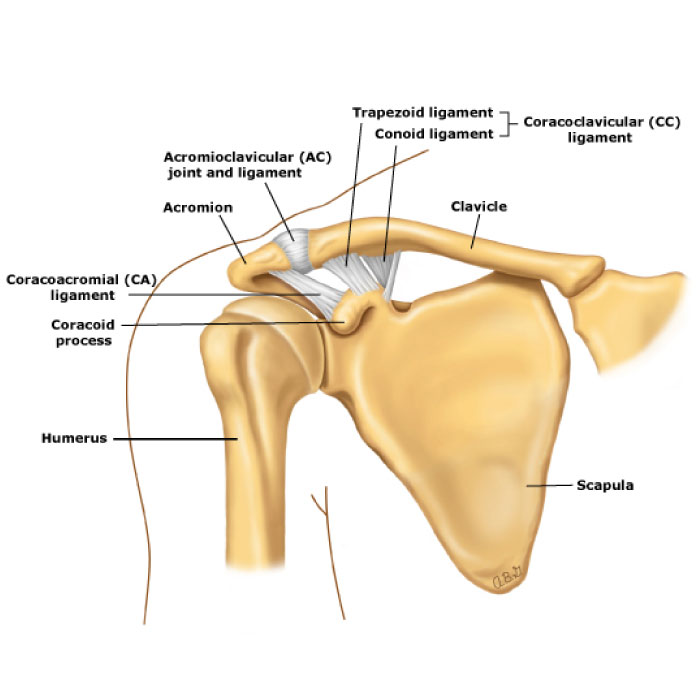

The acromioclavicular joint (also abbreviated to the ACJ) is the joint at the top of the shoulder lying between the outer end of the collar bone (clavicle) and the upper portion of the shoulder blade (acromion). The ACJ and sternoclavicular joints (SCJ) are key links between the arm and central skeleton. The ACJ is reinforced by strong ligaments (the coracoclavicular ligaments) that run from part of the shoulder blade (known as the coracoid) to the collar bone.

The ACJ can be damaged by trauma, infection (rarely), inflammatory and degenerative disease

In many cases of degenerative disease there may be a background of previous trauma or a heavy manual occupation.

Symptoms from the acromioclavicular include pain and instability of the joint. Pain from the ACJ is commonly located on the point of the shoulder.

calcific tendonitis

What is calcific tendonitis?

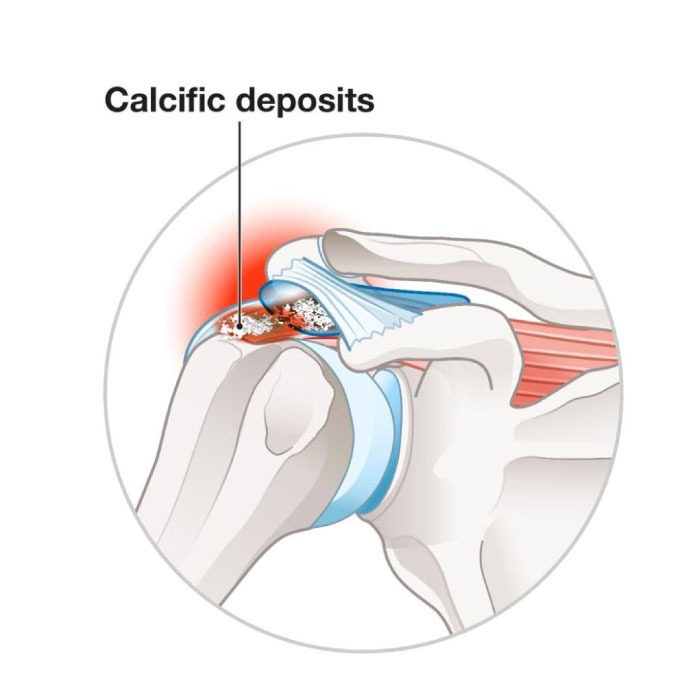

Calcific tendonitis is a condition in which there is calcium build up within one or more of the tendons around the head of the humerus (rotator cuff). It can be extremely painful. These calcium deposits are usually found in patients aged 30-40 years old, and are more common in diabetics. They are not always painful, and even when painful, can spontaneously resolve over a period of weeks.

Why does calcific tendonitis occur?

It is unclear why these deposits form in the rotator cuff tendons. There are different theories proposed, including an alteration in local blood supply and ageing of the tendon. The evidence to support these theories is unclear.

Calcific tendonitis usually progresses in a predictable manner.

There are typically three phases:

Precalcification Phase

Precalcification Phase patients are usually symptom free. There are cellular changes at certain sites within the tendons that predispose the tissues to developing calcium deposits.

Calcific Phase

Calcium is excreted from cells and then coalesces into deposits. The calcium initially looks chalky, not solid. Once the deposits have formed, a so-called resting phase begins. This period is generally not painful and may last a varied length of time. After this resting phase, a resorptive phase begins where the calcium begins to dissolve. This is usually the most painful period. During this phase, the calcium deposits has the texture of toothpaste.

Postcalcific Phase

This is usually a painless stage, as the calcium deposit disappears and is replaced by more normal looking tendon.

Pain as a result of calcific tendonitis is thought to be caused by pressure within the tendon and chemical irritation. A large deposit can cause a block to the elevation of the arm, as it becomes trapped between the head of the humerus and the acromion, causing ‘impingement’.

Your surgeon will usually be able to diagnose this condition on the basis of your symptoms and an examination in conjunction with an X-Ray, ultrasound or MRI scan.

The condition is generally self-limiting, but can cause significant restriction of shoulder function in the short to medium term.

Physiotherapy: To prevent any further stiffness and help to maintain a good range of motion.

Medication: Painkillers and Anti-Inflammatories to treat the symptoms.

Injections: To reduce inflammation and provide pain relief.

Surgery: Surgery may be recommended in the following situations:

Where symptoms continue to progress despite treatment

When constant pain interferes with routine activities (dressing, combing hair).

Where symptoms do not respond to conservative care

Treatments include needling and aspiration or removal of the calcium deposit using key-hole surgery.

Needling (also medically known as ‘barbotage’) can be done either under ultrasound control or as an arthroscopic (keyhole) procedure . A large needle is directed into the calcium deposit and an attempt made to suck out as much of the calcium as possible. An injection of saline or cortisone can be performed into the calcium deposit.

Removal of the deposit is a larger procedure, but can be necessary, especially in chronic cases. This would normally be performed either through a small incision or by key-hole surgery.

Shock Wave Therapy: There are several studies reporting the successful treatment of longstanding calcific tendonitis using shockwave therapy. The technique is thought to work by producing localized ‘microtrauma’ which stimulates blood flow to the affected area. Side effects and complications are minimal, although some localized bruising can occur.

Rotator Cuff Tear

What is the rotator cuff?

The rotator cuff is made up of the four tendons that connect the muscles of the shoulder blade (scapula) to the upper arm bone (humerus). These help control the movements of the ball and socket joint of the shoulder. The four tendons are supraspinatus, infraspinatus, subscapularis and teres minor.

A complete tear will not heal by itself. In these cases, surgery is the only means of repairing a tear. The aim is to improve shoulder function and comfort by repairing any tears in the tendon and if necessary reattaching the tendon to bone.

During the consultation with your surgeon, you will have the scans reviewed in the context of your situation. From this there will be an assessment as to how repairable the complete (full thickness tear) is and whether it can be repaired, or needs reconstructing. The aim of surgical treatment is to improve shoulder function and comfort. Repairing the tendon means reattaching the tendon to the bone, while reconstructing means adding a patch graft between the end of the tendon and the bone.

Physiotherapy is usually needed in conjunction with surgical repair or reconstruction. A tailored rehabilitation programme helps with pain relief and also helps patients maintain and regain function.

The success of surgical treatment depends on the size, thickness and location of the tear and the quality and amount of remaining normal tendon tissue. Early treatment is generally preferred, as the outcome of surgery is often worse when a tendon has been torn for some time

Frozen Shoulder

What is a frozen shoulder?

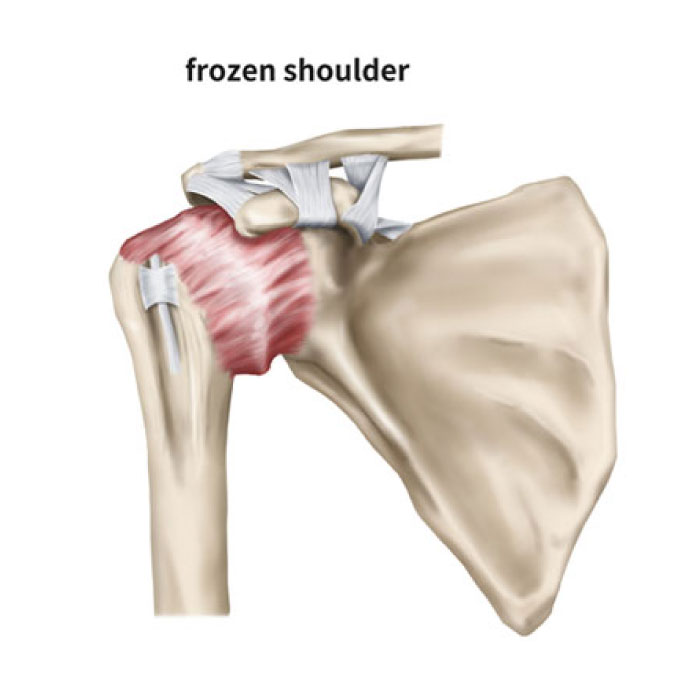

A frozen shoulder (also known as adhesive capsulitis) is often painful with a variable degree of restricted movement.

Why does a frozen shoulder occur?

The condition can be associated with a number of conditions including diabetes, immune disorders, trauma or surgery and in many cases the cause is unknown. The capsule of the shoulder is usually a loose elastic structure, lining and surrounding the glenohumeral joint. In frozen shoulder, this capsule becomes inflamed, stiff and contracted.

The condition usually passes through three phases – starting with pain, followed by stiffness and finally a stage of resolution as the pain eases and movement returns. This process may take some time and a full range of movement may not be restored.

Stage One: Pain increases with movement and is often worse at night. Progressive loss of motion with increasing pain.

Stage Two: Pain diminishes , but the range of motion has become much more limited.

Stage Three: The condition may begin to resolve. Most patients experience a gradual restoration of motion.

Your surgeon will usually be able to diagnose this condition on the basis of your symptoms and an examination. This may need to be supplemented by an ultrasound or MRI scan in order to rule out damage to the rotator cuff tendons. An x-ray can be helpful in excluding conditions such as osteoarthritis.

What happens if nothing is done?

The condition is generally self-limiting but can cause significant restriction of shoulder function in the short to medium term.

Physiotherapy: To prevent any further stiffness and help to regain range of motion.

Medication: Painkillers and anti-inflammatories.

Injections: These can be done to reduce inflammation and provide pain relief. They also can used to perform a procedure called hydrodilatation. Which is used to expand the capsule like a balloon.

Surgery: This involves manipulation of the shoulder while the patient is under anaesthetic in most cases. It may be necessary to perform a surgical release of the tight shoulder capsule using arthroscopic ‘keyhole’ surgery. This can be of benefit in both the early and later stages of the condition. It can provide pain relief and help restore movement. Intensive physiotherapy is essential after surgery.

Why choose iROS?

iROS Ortho Center is a multidisciplinary orthopedic center offering non-surgical and surgical treatment options including orthobiologics, physiotherapy or surgery to treat a wide range of joint pain indications.

- Expertise and Experience

- Patient-Centric Approach

- Simplifed Treatments

- Innovative Care